1.2 The Introduction and Spread of Coloured Grounds in the Netherlands

Across all centres, the data suggest that ground colour choices were not arbitrary but reflected both functional and aesthetic purposes. Painters used coloured grounds to save on costs, speed production, and achieve tonal unity. The broader adoption of coloured grounds therefore coincided with shifts in artistic priorities: the desire for expressive light effects, efficiency of execution, and responsiveness to an expanding art market.

For several decades, scholarship on coloured grounds has been shaped by the influential 1979 article by Hessel Miedema and Bert Meijer, which proposed that the technique was imported from Italy and accompanied the transition from panel to canvas.1 The DttG database now allows this long-standing hypothesis to be tested empirically and reframed as a more nuanced, regionally specific history of introduction and diffusion.

Evidence from early sixteenth-century panels demonstrates that experimentation with tinted preparations began earlier than previously assumed. Artists such as Jan Gossaert (1478–1532) and Maarten van Heemskerck (1498–1574), both of whom later travelled to Italy, had already employed pinkish or greyish ground layers before their journeys south. These early examples suggest that awareness of the pictorial and technical potential of coloured grounds was already embedded in Netherlandish workshop practice and did not rely solely on southern prototypes.

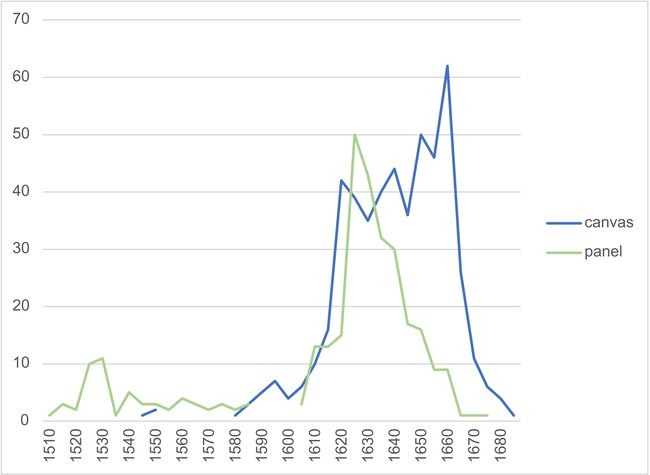

Equally important, the DttG data demonstrate that panel painting, and with it the use of coloured grounds on panel, persisted well into the seventeenth century. This continuity undermines the notion that coloured grounds were tied exclusively to the adoption of canvas. While the overall share of panel paintings declined, especially after 1620, they remained a significant proportion of the sampled works, indicating that the use of coloured grounds was never contingent on support type alone. Figure 1.5 charts the proportion of panels and canvases with coloured grounds across the period, illustrating this sustained overlap.

This project also revealed that the painters who first adopted darker grounds on canvas, long cited as evidence of Italian influence, often maintained stronger ties to France than to Italy.2 This French connection points to multiple and overlapping routes of transmission, although this particular avenue requires further study.3 Rather than a single moment of importation, the evidence reveals a slow, non-linear evolution of the practice within the Low Countries.

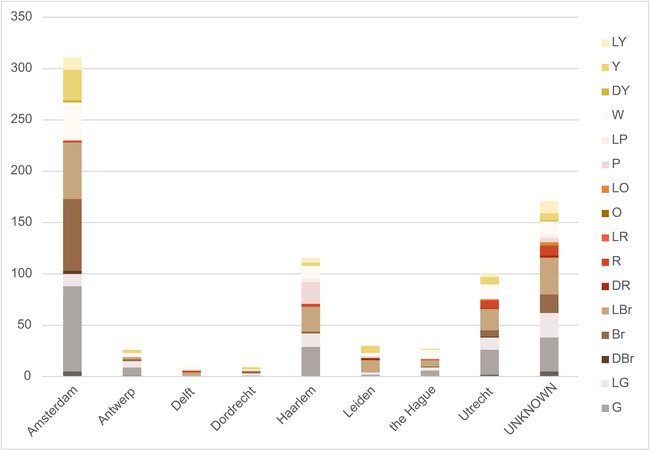

Between roughly 1590 and 1630, coloured grounds were adopted across the Netherlands with remarkable speed. Landscape painters such as Esaias van de Velde (1587–1630) and Jan van Goyen (1596–1656) employed light grey and brown grounds to unify their compositions tonally and to paint more efficiently.4 In Utrecht, Abraham Bloemaert and his peers Paulus Moreelse (1571–1638), Joachim Wtewael (1566–1638), and later the Utrecht Caravaggisti, embraced darker red and grey grounds to heighten chiaroscuro effects and to translate Italianate styles and compositions into local idioms.5 Amsterdam’s painters, many of whom were engaged in portraiture and genre painting, tended toward paler, neutral double grounds that facilitated subtle modelling and controlled surface finish. Figure 1.6 shows top ground-layer colours by city; the prominence of Amsterdam largely results from the extensive technical study of Rembrandt and his workshop.

Figure 1.5: Panel versus canvas supports in Netherlandish paintings 1500-1680 (data collection drop after 1650). (Figure adapted from M. Hall-Aquitania, “Common Grounds: The Development, Spread, and Popularity of Coloured Grounds in the Netherlands 1500–1650” [PhD diss., University of Amsterdam, 2025], fig. 1-11.)

The spread of coloured grounds was closely tied to changing modes of artistic production. The early seventeenth-century art market demanded faster and more flexible working methods, and coloured grounds offered a tangible process innovation: they reduced the need for laborious underpainting, provided immediate tonal unity, and enabled looser handling, often allowing the colour of the exposed ground to contribute to the composition. At the same time, the rise of professional primers (specialists who prepared supports for sale) helped to disseminate these practices on an economic and practical level, standardising materials and leading to more consistent ground types across market segments.6

Intellectual and theoretical developments further encouraged this transformation. Painters and writers of the period were increasingly attuned to optical phenomena and to the representation of light as a structuring element of painting. Karel van Mander’s Schilder-boeck (1604) and Samuel van Hoogstraten’s Inleyding tot de hooge schoole der schilderkonst (1678) both emphasised the harmonious balance of light, tone, and colour as the foundation of pictorial excellence.7 Coloured grounds provided a material means of achieving these ideals: they often worked as a mid-tone, facilitating subtle modulation between light and shadow, and contributing to the atmospheric coherence so prized in seventeenth-century painting.

The combined evidence from technical data, art-historical context, and economic history thus redefines the adoption of coloured grounds as a multifaceted process rooted in local innovation and cross-regional exchange. Rather than a derivative import from Italy, coloured grounds in the Netherlands emerged from an evolving dialogue between material knowledge, artistic ambition, and market dynamics—a transformation in painters’ material thinking that mirrors the broader redefinition of painting as both craft and intellectual pursuit in the early modern period.

Figure 1.6: Topmost ground layer colours by city of execution, 1500-1690 (data collection drop after 1650). See DttG Colour Checker for colour codes. (Figure adapted from M. Hall-Aquitania, “Common Grounds: The Development, Spread, and Popularity of Coloured Grounds in the Netherlands 1500–1650” [PhD diss., University of Amsterdam, 2025], fig. 1-8.)

Notes

1 Hessel Miedema and Bert Meijer, “The Introduction of Coloured Ground in Painting and Its Influence on Stylistic Development, with Particular Respect to Sixteenth-Century Netherlandish Art,” Storia Dell’arte 35 (1979): 79–98.

2 See Chapters 2 and 5 of Hall-Aquitania, “Common Grounds,” 63–95 and 179–227.

3 For an overview of early coloured grounds in France, see Stéphanie Deprouw-Augustin, “Colored Grounds in French Paintings Before 1610: A Complex Spread,” Journal of Historians of Netherlandish Art 17, no. 2 (forthcoming 2025).

4 See Chapter 3 of Hall-Aquitania, “Common Grounds,” 97–129. Also Melanie Gifford, “Style and Technique in the Evolution of Naturalism: North Netherlandish Landscape Painting in the Early Seventeenth Century” (University of Maryland, 1997).

5 Hall-Aquitania, “Common Grounds,” 179–227.

6 Moorea Hall-Aquitania, “Prepared and Proffered: The Role of Professional Primers in the Spread of Colored Grounds,” Journal of Historians of Netherlandish Art 17, no. 2 (forthcoming 2025); Hall-Aquitania, 97–129.

7 See Chapter 4 of Hall-Aquitania, 131–77.