1.1 Common ground types in the Netherlands 1500-1650

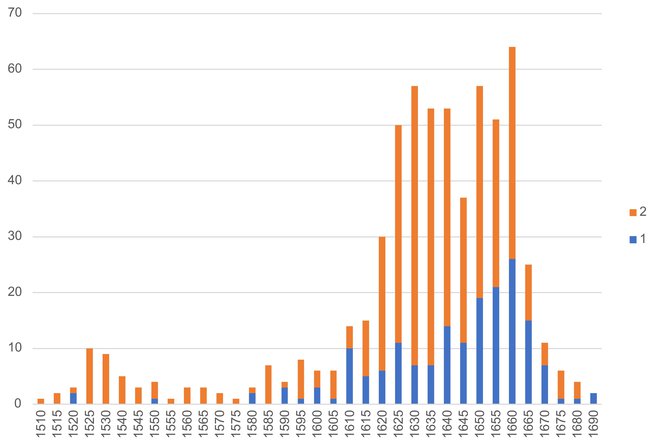

The Down to the Ground (DttG) database brings together over 830 records of Netherlandish paintings analysed for their preparatory layers, forming the most extensive resource on coloured grounds to date. The data reveal both continuity and experimentation in ground preparation practices between 1500 and 1650. Throughout this period, most Netherlandish paintings employed double grounds (Figure 1.3)—a coloured or white first layer (depending on support) and a neutral-toned second layer—but the materials, colours, and functions of these layers varied according to support, workshop, and period.1

To ensure clarity across a wide range of ground layers and supports, the DttG project follows the terminology developed by Maartje Stols-Witlox in A Perfect Ground.2 She defines a preparatory layer as “a layer applied to the entire surface to be painted,” and a ground as a preparatory layer consisting of pigments in a binder. Each ground layer is numbered from the support upward: “first ground layer,” “second ground layer,” and so forth, rather than using ambiguous terms such as imprimatura. The colour, composition, and thickness of each ground layer can be added for specificity. This system is well-suited for describing the multi-layered preparatory systems typical of sixteenth- and seventeenth-century Netherlandish painting.

On panel supports, traditional chalk-and-glue grounds remained dominant well into the seventeenth century. Painters typically applied multiple coats of fine chalk mixed with animal glue, producing a smooth surface ideal for meticulous brushwork. This chalk-based first ground was highly absorbent and needed to be isolated before oil-based paint layers could be applied. It is in this second ground layer that subtle tints, such as pale greys, various pinks, and light yellows, began to appear from the early sixteenth century onward, anticipating the more colourful approaches seen on canvas.

On canvas supports, the first ground was most often earth-based and oil-bound, composed of iron-oxide reds, brown and yellow ochres, or clays. These mixtures provided flexibility and were applied more thinly, allowing canvases to be rolled for transport without cracking. Earth pigments were also attractively inexpensive. Although technically possible to paint directly onto this first ground layer, artists rarely did so, particularly when it was dark in colour. The frequent use of neutral-toned second grounds suggests that these second layers were primarily intended to “correct” the colour of the first ground.

Figure 1.3: Proportion of single (1, in blue) to double (2, in orange) grounds in the DttG database, 1510–1690. Only includes database paintings that have been sampled (layer structure confirmed with cross-sections).

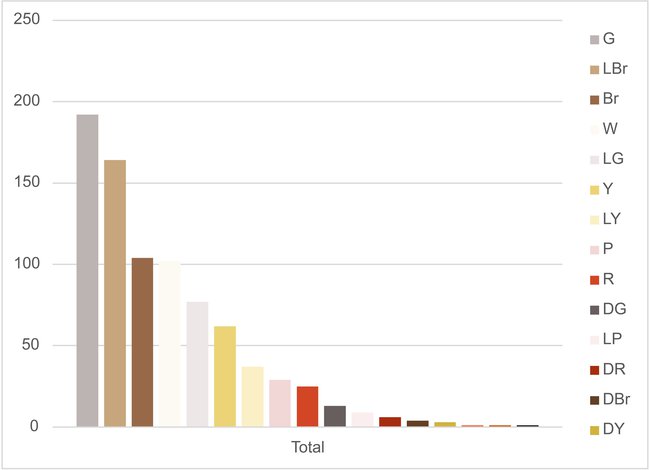

The two-layer system that became characteristic of Netherlandish practice typically combined a warm, opaque red or brown first ground with a light grey or light brown second ground. This construction offered both technical and optical advantages: the darker-coloured, often clay-based first ground filled the texture of the canvas, providing a relatively smooth surface to work on, while the lighter upper ground provided a neutral mid-tone for modelling form and light. Such systems were compatible with a wide range of painting methods, from the tightly controlled finish of fijnschilders to the looser, more dramatic approaches of many history painters. As shown in Figure 1.4, most Netherlandish paintings on both panel and canvas display mid- to light-toned neutral-coloured top grounds, suggesting a general preference for a controlled starting tone for modelling light and colour.

Regional differences are evident, though it must be noted that most technical studies to date have focused on individual artists or specific cities. Haarlem painters, for instance, frequently employed pinkish grounds, perhaps reflecting the influence of a local professional primer or a closely connected cluster of artists sharing materials and techniques. Utrecht painters regularly used light brown or grey over red double grounds, likely reflecting both the materials provided by local suppliers and the teaching of Abraham Bloemaert (1566–1651), whose workshop played a key role in transmitting this practice. The most extensive research on Amsterdam painters remains that of Karin Groen, who examined the grounds of Rembrandt (1606–1669) and his contemporaries.3 Her identification of numerous grey over red grounds within this circle has since been refined by later studies, as discussed in section 1.3.

Beyond Rembrandt, detailed analyses exist for artists such as Jan Steen (1626–1679) and Frans Hals (1583–1666).4 While these investigations provide valuable insight into individual working methods, they cannot on their own capture broader material patterns. The DttG database brings together the widest possible range of available evidence to begin addressing this imbalance, but important gaps remain. Expanding the dataset to include a wider range of contemporaries is essential for developing a more representative picture of seventeenth-century painting practice, one that will continue to sharpen and evolve as new data are added.

The material diversity revealed in the DttG database provides the foundation for understanding how and why coloured grounds were adopted across the Netherlands. The following section traces their chronological development and regional diffusion, situating these technical observations within broader artistic, economic, and theoretical contexts.

Figure 1.4: Topmost ground layer colours in the DttG database. See DttG Colour Checker, discussed in more detail in section 2.4, for colour codes. (Figure adapted from M. Hall-Aquitania, “Common Grounds: The Development, Spread, and Popularity of Coloured Grounds in the Netherlands 1500–1650” [PhD diss., University of Amsterdam, 2025], fig. 1-6.).

Notes

1 Larger trends are discussed in Chapter 1 of Hall-Aquitania, “Common Grounds," pp. 33-60.

2 Stols-Witlox, A Perfect Ground: Preparatory Layers for Oil Paintings 1550-1900, xi–xiv.

3 Karin M. Groen, “Grounds in Rembrandt’s Workshop and in Paintings by His Contemporaries,” in A Corpus of Rembrandt Paintings, IV (Dordrecht: Springer, 2005), 318–34.

4 Albrecht et al., “Jan Steen’s Ground Layers Analysed with Principal Component Analysis”; Marya Albrecht et al., “Discovering Trends in Jan Steen’s Grounds Using Principal Component Analysis,” in Ground Layers in European Painting 1550-1750, ed. Anne Haack Christensen, Angela Jager, and Joyce H. Townsend, V, CATS Proceedings (London: Archetype Publications, 2019); Groen and Hendriks, “Frans Hals: A Technical Examination.”