1. Coloured Grounds in Netherlandish Painting 1500-1650

Coloured grounds offer a revealing point of entry into the working practices of early modern painters. They represent a distinct and important step in the painting process but are often covered up by later layers. In this way, they provide unique insight into the painter’s practice. This includes the decisions that shaped the construction of the painting, such as the choice of support, preparation materials, and intended manner of painting (ranging from fine and detailed to looser and more expressive, or anywhere in between), as well as the depiction of convincing light and space on the painted surface. Introduced in the sixteenth century, by the mid-seventeenth century, coloured grounds became both technically and aesthetically integral to Netherlandish painting practice.

During the crucial decades 1590–1630, painters across the Northern Netherlands adopted coloured grounds with remarkable speed. The DttG database makes it possible to visualise this transition and to test longstanding hypotheses about origin and popularity. This project is part of a larger movement towards understanding the qualities and function of preparatory layers, along with art technological source research particularly that by Maartje Stols-Witlox, and targeted, in-depth case studies by conservators and scientists, notably at the Frans Hals Museum, the Mauritshuis, and the Statens Museum for Kunst.1 This research builds directly on earlier research to create a more comprehensive picture of the use of coloured grounds during this period and what their popularity tells us about artistic process and intent.

By combining new research with existing data from conservation studies, museum archives, and published analyses, the project enables transparent comparison across regions and artists. The resulting patterns suggest that coloured grounds were not a single imported innovation, but a multifaceted practice adapted to local materials, workshop traditions, and market conditions.

Figure 1.1:

Hendrick ter Brugghen

De roeping van Mattheus, 1621 gedateerd

Utrecht, Centraal Museum, inv./cat.nr. 5088

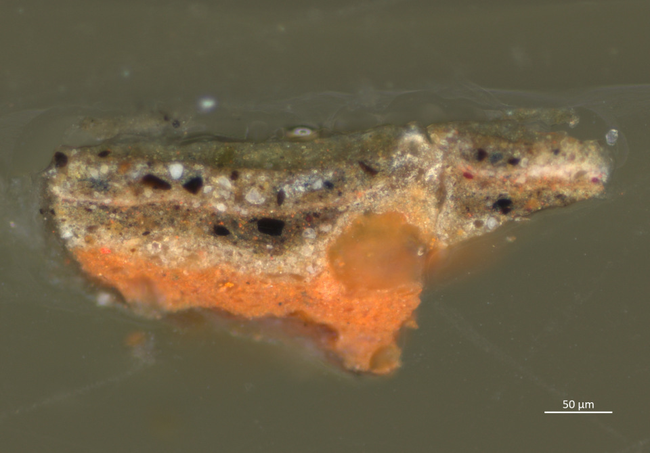

Figure 1.2: Cross-section (A288-7, 200x magnification, dark field) of Hendrick ter Brugghen, The Calling of Saint Matthew, 1621, oil on canvas, 102 x 137.5 cm, Centraal Museum, Utrecht. Photographed by Moorea Hall-Aquitania.

Notes

1 Maartje Stols-Witlox, A Perfect Ground: Preparatory Layers for Oil Paintings 1550-1900 (London: Archetype, 2017); Ella Hendriks, “Haarlem Studio Practice,” in Painting in Haarlem 1500-1850: The Collection of the Frans Hals Museum (Ghent: Ludion, 2006), 65–96; Karin Groen and Ella Hendriks, “Frans Hals: A Technical Examination,” in Frans Hals (Munich: Prestel-Verlag, 1989), 109–27; Marya Albrecht et al., “Jan Steen’s Ground Layers Analysed with Principal Component Analysis,” Heritage Science 7, no. 53 (2019): 53; Maartje Stols-Witlox and Lieve d’Hont. “Remaking Colored Grounds: Reconstructions for Art Technical and Art Historical Research.” Journal of Historians of Netherlandish Art 17, no. 2 (forthcoming 2025); Marya Albrecht and Sabrina Meloni. “Laying the Ground in Still Lifes: Efficient Practices, Visual Effects, and Local Preferences Found in the Collection of the Mauritshuis.” Journal of Historians of Netherlandish Art 17, no. 2 (forthcoming 2025).